Versione Italiana qui

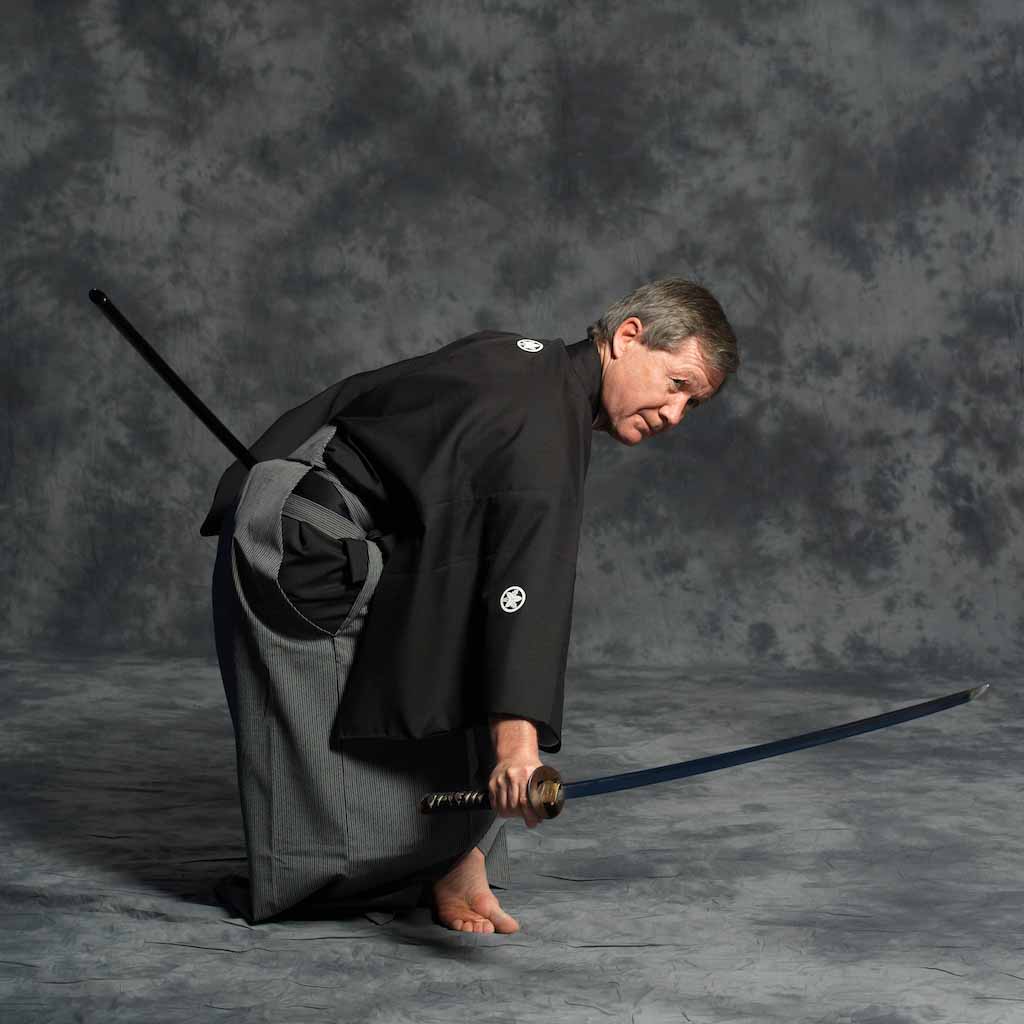

Kiryoku team traveled this month across the Alps to the Occitania region to meet a leading figure of French and European Iaido, Jean Jaques Sauvage, Iaido 7°dan Kyoshi and Kendo 5°dan. From the first steps in Judo to the highest degrees in the art of the sword, it is a pleasure to be able to hear the depth of his thoughts on the typical themes concerning the history, development and personal vision of our disciplines, in a breakneck race through details and anecdotes of a sensei who cares far more about the awareness of being able to give and transmit than the status within a dojo, with a knowledge that comes from having deepened the details of the Way with the calmness and the support of the many figures who accompanied him along his growth path.

Sauvage sensei, as always, it is an honour for Kiryoku to be able to take advantage of spending some time with persons like you, and to be able to learn directly from the pioneers of the art of the sword any thought and teaching resulting from a life of learning.

Let’s then obviously start from the beginning with some biographical notes to better frame your figure also for those readers and practitioners who might not know you yet.

I was born on December 9, 1947 in Lisieux in Normandy. I came to Versailles from 1975 to 2005 and having never been able to resist the calling of the sun, I now live in the south of France near Narbonne.

I am retired now, but I was a physical education and Judo teacher, and I got Iaido Kyoshi 7th dan as well as Kendo 5th dan and Chanbara 5th dan.

Having spent a whole life with martial arts, he will surely have had the opportunity to learn and work alongside many sensei: which are the figures to whom he owes the most recognition for having contributed to his personal growth and why?

My gratitude is great and my infinite respect goes to my Judo master (1966-74) Jean Pilorge who inspired me about audacity in defiance of obstacles and dangers, to believe in our boldness to dare to be oneself, that it was not necessary to hope to undertake, nor to succeed to persevere and that the greatest efforts of man to surpass himself are in vain if, beyond himself, he is still looking for himself, and not for a superior reality.

The study of Kime No Kata, for the State Certificate of judo teacher in 1971-72 at the CREPS of Houlgate in Normandy, brought me closer to the Japanese sword. A Kendo-Iaido initiation course led by Jacky Vauthrin in Lisieux in 1973-73 stimulated my curiosity.

Roland Degorce my second Judo teacher (1975-79) in Versailles obliged us to bring to mind rigor, patience, beauty and efficiency of form, humility with constancy, courage and persévérance, knowing how to wait to mature, to correct ourselves, to recover and to stimulate our enthusiasm about what remains hidden or ignored, on top of enduring iniquity.

Brother Pantel, director of the Saint Nicolas college in Igny, had a brilliant culture and his confidence built me.

Kendo experts (practicing Iaido) seconded from the ZNKR Hiroyuki Shioiri sensei in 1977-78, Mineo Nakayama sensei 1979-80, Nobuo Hirakawa sensei 1980-81, Itsuo Naito sensei 1985-86, Mutsunori Ishiyama sensei 1990-91, Makoto Higashiyama 1993-94… and the summer camps in Japan (Kitamoto-Seitama) accompanied me until a story took shape.

There have really been so many people on your growth path, and it is nice to learn how each one has left a distinctive mark on your path. Fifty years have gone by since you first approached the art of the sword, a significantly long period of time that should allow to talk about the differences with current times and how the French environment was at the beginning: would you like to tell us something about that times when everything was to be built?

Before 1993 the French aido was a clan story. At the time there was a feverish craving for novelty that didn’t know exactly what it wanted except the desire for something else. With a desire to do well embedded in the body and my desire to interest practitioners, I have, through multiple, innovative actions, federated the French Iaido increasing the membership from 400 to 1930.

To respond to the patience of the impatient, I organized the first national courses supervised by Japanese delegations.

I created the Teaching Commission and its BFEI (French Iaido Teaching Certificate), a France Group accessible to all to create a French team as well as the Arbitrage Commission.

I fulfilled my moral contracts by becoming a teacher, trainer, examiner, competitor, selector, DTR (Regional Technical Director) in Yvelines, Languedoc Roussillon and in the PACA region, DTN (National Technical Director) from 2001 to 2006, then referee (Kendo, Iaido, sport Chanbara), juror of examination at regional, national and European grades.

Impressive, and I would dare to say that he was unstoppable in developing this discipline at a national level, and beyond: such a strong passion must necessarily have a propulsive thrust out of the ordinary. What does Iaido mean to you and what does it offer you?

Iaido and Kendo revealed to me the nobility of gesture more than the power of words. With passion I tried to find, with sincerity I tried to understand, with reserve I dared to share.

I took the words that legend and tradition inspired me, not to put my mark on them but to touch on plenitude, purity and beauty. I do not seek to impose my truth, just to enlighten it to perceive that the gestures of Iaido and Kendo are far beyond aesthetics. It is always between weightlessness and lightness, between power and fragility, between the inside and the outside. It is because its form is never actually definitive that it is the fruit of a permanent search, of an ideal of perfection specific to the martial art.

Through these fratricidal duels, I assumed national responsibilities, in order to participate in the evolution of certain actions, to draw the courage to accept inertia, to know differences through wisdom. The history of men is never more than the history of their own war. It’s up to everyone to start it over. A war that we wage on ourselves to escape that of others.

If beauty occurs, it is because the quality of the movement no doubt serves the idea perfectly.

But is the idea enough to create beauty? It is impossible to answer. I only believe that it is when we touch the very essence of things that we give birth to beauty. A way of also affirming that what it gives us to see is above all the result of an encounter, of a transformed perception, and this to offer us these cuts, then these moments of grace and dazzle, to reach the end of the journey that hence never began!

How did your relationship with the Japanese sensei begin and what among their qualities allowed you to progress along your path of growth in Budo?

It all started in 1993 with Versailles Budo when I was in charge of the CNKDR’s Iaido commission (Comité National de Kendo et Disciplines Rattachées). From April 1995 to February 2008, I organised, with the CNKDR agreement, more than 40 national courses in the presence of Japanese delegations.

Despite numerous requests from the Japanese Sensei, I was forced by my position, unable to attach myself to a Sensei.

Their landmarks are lairs and vice versa. [it’s a French wordplay : Landmark = repère, lair = repaire].

They are secret beings, with natural dignity, who speak a little. They are standing men who are just passing by. What matters is not where do they come from but what they give.

They have common themes that structure their stories. They are often the same and yet everyone treats them with their own sensibility, so that the palette is enriched with each encounter and the picture painted has nuances that constitute its flavor and value.

They have the eyes of the inner journey or those of the unfathomable. They are a path that brings us back to forgotten lands, makes us discover the traces of an era that has become dust and brings to light what had been the life of those who, lying under the stone, returned to the heart of earth.

Discreet, delicate men, attentive to human nature and their passions, they throw out a distant eye on the world from which it is impossible to tell whether it is worried or amused.

They believe in the voluptuousness of arid paths and affirm that the posture has only one syllable to switch into imposture. In front of the violence of the world, the brutality, the vulgarity or the mediocrity of behavior, they slay the wear and tear of time to make man wiser and less bitter.

Men of heart, they possess that precious quality despised by the arrogant: kindness. They cultivate a taste for discretion as a way of life, an art of elegance.

Their gaze itself alone is a direction. They have the look of the inner journey which touches at the truth of beings, at the secrets of hearts and the depths of the soul.

They abandon themselves only in moments of great distress and reveal at this moment a deep disarray.

Did I dream of these encounters? Are they true?

Who is your reference sensei and consequently which ryu did you approach?

I discovered Muso Shinden Ryu under the teaching of Jean Pierre Raick sensei, my teacher, as well as Tamiya Ryu. I practiced a little Hoki Ryu with Hiroyuki Konaka sensei.

Hikoshiro Sato sensei prepared me for 6th dan and Takashige Yamazaki sensei for my 7th dan.

In your extensive experience, have you been able to realize any obvious differences between the Japanese and Western teaching models or are there particular overlapping points?

Dojo is a very strong symbol of Budo, a place of life, of progress, a place where a spirit blows, from where harmony and serenity are born from encounters between men, functions, abilities but also expectations, beliefs, chances, unspeakable certainties.

I have learned that in the pedagogical field there is no ideal recipe, ideal teacher, ideal student performing an ideal kata in front of an ideal jury, under the eyes of an ideal Sensei.

The essential is to be because the teacher can only recognize himself where he is engaged.

The teacher should raise the student as he himself would like to be, lead him to where he himself would like to be.

Speaking about approach, how does a practitioner approach this discipline for the first time, what reasons guide his choice according to your experiece?

Any practitioner, in his beginnings, is confronted with the rigor of the practice, with this precision of the gesture and the need to express himself through a rigid and precise framework. Initially, he may feel frustrated and even constrained by the details of the gesture. Little by little, he accepts this rigor and understands its necessity. Then comes the time when we want to know why we practice and not how?

Why do we practice Muso Shinden Ryu and not Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu, Shinkage Ryu, Tamiya Ryu, Katori Shinto Ryu, Hoki Ryu, Suio Ryu or Tatsumi Ryu for example? There is no truth but judgments of taste relating to particular intellectual, conceptual, historical or ideological configurations. Whatever the Ryu chosen, it is above all a question of cultivating the pure gesture.

What is pure gesture? It is the gesture rid of ambition, anxiety, the will to do that draws its origin from the “ego”. The pure gesture is a fruitful thought when it awakens the conscience of what is not right. It is a language to feel the world and the place it occupies in it. Don’t lock him up, don’t hold him back. Its lightness accelerates its course, frees the technique. It continues at the very moment it stops. The gesture becomes unique by what it does when it does it. It liberates the being and not the seeming. The gesture guided by a serene and free spirit, unveils its soul and reveals the hand of the master.

They all seem to me deep thoughts that can only have developed through a very careful introspective path, a sign of a precise will, as you also mentioned at the beginning, to comply with some moral duties such as teaching. When did you start thinking about this phase?

My first steps in Judo took place in 1970 in Vimoutiers (Normandy).

My first steps in Kendo-Iaido go back two years before the creation of Versailles-Budo in September 1979. It was at this time that I began to teach Kendo and Iaido without any particular requirements having at the base a training course of teacher. In the 2000s we were 120 members.

And in all this time and with all the transformations that you will have seen, is it possible to outline the changes that have characterized this discipline over the years and what is its goal today?

The iaido has changed, it aspires to go out of its framework to become a tool for self-knowledge and personality development. Its mission is not only intended to transmit knowledge or know-how but also to light fires: the fire of attention – the fire of astonishment – the fire of courage, determination, freedom to to be oneself – the fire of passion, of sharing – the fire of a true human adventure.

It is to breathe its own origin and its own end, to tend towards starkness, to grasp its deep resonances.

Teaching prevents being too quiet, from withering away. We don’t teach what we want. I would even say that we don’t teach what we know or what we think we know. We teach and we can only teach what we are. The main thing is to be and it can only recognize itself where it is engaged.

From changes to transformations to objectives, and even only remaining within the limited temporal space of a lesson, there will certainly be some critical points that you address while teaching: how are these principles reflected in one of your Iaido lessons?

Art, since the origin of the world is only movement. It is born from constraints, lives from struggles and dies from freedoms. He looks for the life and the thrill of the human soul at the heart of a cultural heritage which is not his own but which builds him.

Understanding what we live and what we are. Feeling what can be said and what can be kept quiet.

He draws the sword out of its scabbard, with the same movement, the same assurance. With a calm and serious gaze, he lets movement arise within him to reveal the three dimensions of time. The present of the past is memory. The present of the present is vision. The present of the future is waiting.

The fear of repetition is always present. It completes the unfinished process of metamorphosing into the art of life.

A breath, a shadow, a mere nothing… He confronts the void to cultivate the correctness and courtesy required, the discipline that must be observed, the humility that must be felt and the sincerity that must be applied. Birthless and endless, perfection and imperfection come together to express the invisible through the visible. They are like a frozen shadow before reaching their goal without the will nor the hope to be bigger or stronger. They only take shape through the erasing of their own trace in the perception of the other.

This journey rises through authenticity, veracity, fidelity to reach this aesthetic and spiritual superiority… to go to the essential, again and again, which remains the most difficult to reach… to find the silence that creates, kneads, sculpts the human being in him.

What the Katana cuts in the last step is what flows inside it and not what exists outside of it. He watches his blade for a long time, then with a brief smile he cleans it of its clumsiness and slips it into the bottom of its sheath.

The next day, the same scene repeats.

What do you think is an urgent imperative to guarantee the constant improvement of this discipline, through the great cultural and philosophical load that it carries with it?

There is an urgent need for leaders and teachers to wake up and hear the cultural, martial and spiritual side of Iaido. Otherwise, it will continue to digress to become a simple activity without content, without soul, without particular character.

Looking at them and not seeing them, he calls them the invisible. Listening to them and not hearing them, he calls them the inaudible. Touching them and not reaching them, he calls them the impalpable. Elusive and fleeting, they purify without offending, rectify without constraining, illuminate without dazzling. The one who abandons himself does not speak of it.

A distraught blind man stopped at the sidewalk edge and waited for help. After a few moments, a hand grabbed his arm. The other man didn’t say anything, but together they started down the path. When they had both reached the sidewalk opposite, the stranger loosened his grip and whispered to him: “Thank you, sir, for helping a blind man to cross the street.

Here is an anecdote on the randomness and the falsity of the real. This anecdote is more a matter of fight between darkness and obscurity than of clairvoyance.

So what conclusion can we draw about the future of European Iaido and what should we do to promote its values?

The answer to this legitimate question seems to emerge quite clearly.

I think that Iaido occupies an essential place in the European landscape. It highlights the importance of courtesy and mutual respect. It strengthens peace and prosperity among all federations. Staying loyal to its origins, it grows reasonably with wisdom and efficiency. Nevertheless, the Japanese delegations remain essential to our journey.

The values involved here are so many and they are profound, they fully convey the concept of a Way. The aspect of the approach to the discipline is still central to this interesting discussion and we have already talked about the reasons that push a neophyte to the art of the sword. How then do you present all these concepts to a still inexperienced practitioner and what advice would you give him to consolidate his interest?

I would simply answer him that the supreme force of art is to force us to will to exhaust the inexhaustible in it. I would start by unteaching him the forms acquired in the other disciplines.

I would invite him to abandon himself to the forms of time, to elude his certainties, to dare to see and think differently, to be curious in order to experience the human soul…and finally to be.

I would wish him to love what must be loved and to forget what must be forgotten.

I would wish him passions, silences, to resist the stagnation and indifference, the negative virtues of our time.

“Failing to discover what you are, gradually cease to be what you are not. You will then become the best you can be!

Find joy in what is simple and free of charge, because happiness is not a destination to be reached but a way to travel!”

Going back once again to a more general aspect, and also by virtue of the name chosen for your school in Versailles, which teaching of Budo do you feel particularly as kindred and therefore you like to transmit?

The teacher’s responsibility when judging is not to exercise hegemony over practitioners… Apart from the criteria defined by the ZNKR Iai, our benevolence must seek more to enhance than to sanction. It should strive to see their gaze, take into account their risk-taking, their audacity, their confrontations, their limits, perceive their emotionality and the incompleteness of their gestures to inscribe it in a space where it would simply offer him the right to be.

We have just incredibly reached the conclusion of our meeting, time has literally flown by in your company, discussing aroud profound themes that characterize the different aspects of progression onto a Way. While thanking you again for the time you dedicated to us so far, it has been a true pleasure, but it is our habit to close with an anecdote that characterized the practice of a sensei and we would like to ask you to tell us something special that provided you with further food for thought and which may be indicative of the your particular approach to the practice of the art of the sword.

A day of tiredness, without complaining about my bloody knees, my feet which refused to slip, Soo giri posed a problem to me… Irritated and furious at my incomprehension, Sensei tried with firmness, rigor and precision to explain my shortcomings, with careful, calligraphic phrasing.

Coming to the rescue of my distress, he asked me to follow him out of the town of Ageo, to a friend who owned a piece of wooded land. And here we are in the middle of the bamboo, with our swords. From our cuts, horizontal, diagonal and vertical energies emerged to create a space where the gaze and the breath wandered from surface to depth, from tangible elements to sensations…

What was he trying to convey? Mastering the different cutting angles (Hasuji)? The perfect use of Te no uchi, Furi kaburi, Mono uchi? The sword mass? The breath of the blade (Tachi kaze)? Find the soul of each gesture? Bringing the sword to life, which becomes an extension of oneself? He seemed delighted with this experience, then without saying a word he walked away for a moment, leaving me with myself.

In this nature I felt the silence and in the hollow of its absences, the Katana became verb.

“You, traveler who discovers me… To dive into my arteries and my alleys, you have to agree to abandon yourself to the tumult of lives, which as soon as dawn electrifies me.

We don’t cut in the place, we cut the place.

What you cut in the last step is what flows inside you.

I open my doors to you on fratricidal duels.

I bring you content to create reciprocity,

I reveal to you my heritage,

I am a vehicle for civilization. This is one of the great challenges of modern life. This duty that we now have to take the other into consideration, to think about the type of relationship we will have with this other with whom we are constantly confronted. We can do it in fear or anger, or in a more intelligent and positive way.

I propose to everyone to be one of a heritage guardians, to be among those who will enrich it, to also be a baton passer.Self-control is eternal, soothing, no longer letting urgency wins over essentials.

Undereneath my look of great simplicity hides the fury, the suffering and the harshness of a journey through time.

My coldness is that of nostalgia, the face of an anachronistic past threatened by the passage of time, of disillusion.

The sound of my Ha saki, open to all audacity, transcends flesh, desire, adversity, game.

My serenity, in a climate of permanent survival, is a daily challenge to reconnect with the dense and rich icons of the past.

My langage pranks are a pledge of politeness, rigor, honor and fidelity.

That’s why I fascinate you, why I grab you relentlessly, leaving images in your memory that will stay with you for a long time.When the night stretches in shadow on the floor,

When a full moon tears the sky and slips a soothing glow,

In these silences that only the winds disturb,

In this purity absolutely foreign to the human world…

You seem to perceive all the magic I am capable!I am a DO in which it is good to get lost, wander, discover the richness of encounters.

Above all, I look for mind peace to inscribe moments of peacefulness in you.

I am never so desirable as when the incendiary sun sublimates me, empurples my flanks.

He taught me brilliance, fragility and purity,

Perfection and imperfection are a journey that strips man of his artifices, a will to understand, a desire to share, to respect this “other” who reveals to me the essential, the human who is in you!

Time will show you that the teacher’s responsibility is not to exercise hegemony over the student.

With pride I tell you, I am at the service of one of the most beautiful disciplines.”