Anyone who ever made a paper boat or played as a child to make paper frogs jumping has already taken the first steps, perhaps unwittingly, in the art of paper folding. A poor but common pastime, which takes one back to the simple games of childhood, but which actually hides a much nobler and more profound art, origami. This term refers to the art of folding paper, from oru (folding) and kami (paper) and, consequently, the term used as a noun indicates the resulting folded object.

Origami has its origins in China around 105 AD, while in Japan the art spread from the sixth century only thanks to the development of the possibilities associated with the use of paper as a means of a new art: it is therefore easy to imagine it was, at the beginning, an activity practiced by the elite, religious or noble castes, before paper became poor material and therefore could take advantage of a wider diffusion. In Japan the art of paper folding was characteristic of monks for the creation of objects for religious purposes, but many other ceremonies featured folded paper at the center of formal events: origami itself was used for the creation of paper butterflies to adorn sake bottles during weddings, tsutsumi is the art of wrapping gifts with folded paper, synonymous with sincerity and purity, or even the tsuki, folded paper that accompanies a particularly precious gift. Even samurai were known to exchange gifts adorned with the noshi, a kind of amulet of luck made up of strips of folded paper: everything leads us to indicate how origami was a significant aspect of ceremonies, adding a sort of certificate of authenticity to the object itself. And to further underline the highest meaning attributed to this art, it is worth noting that although written with different kanji, the origami contains that “kami” which, despite meaning paper, it happens to be the same Japanese word used to indicate objects or gods of the Shinto religion.

As paper became a more common material, origami also began to be used as an educational tool, since the folding process includes several important concepts even in mathematics studies: the first book on origami, the Senbazuru Orikata (orikata, folded forms, was the original term to indicate this art, while Senbazuru Orikata means the folding of a thousand cranes) is dated 1797, by Akisato Rito, a text written more to spread the culture of origami than the technique itself. Instead, Yoshizawa Akira, often referred to as the great master of origami, is the one responsible for the more general diffusion of origami techniques, with the publication of the book Atarashi Origami Geijutsu (the new art of origami) in 1954, date from which he became a sort of cultural ambassador for Japan for the diffusion of this art in the world. Yoshizawa was responsible for the definition of the origami fold notation system called “Yoshizawa-Randlett system”, which later became a standard for most creative origamists, with which it became easy to represent two-dimensionally, through photos and drawings, how paper should look folded to obtain the desired shapes.

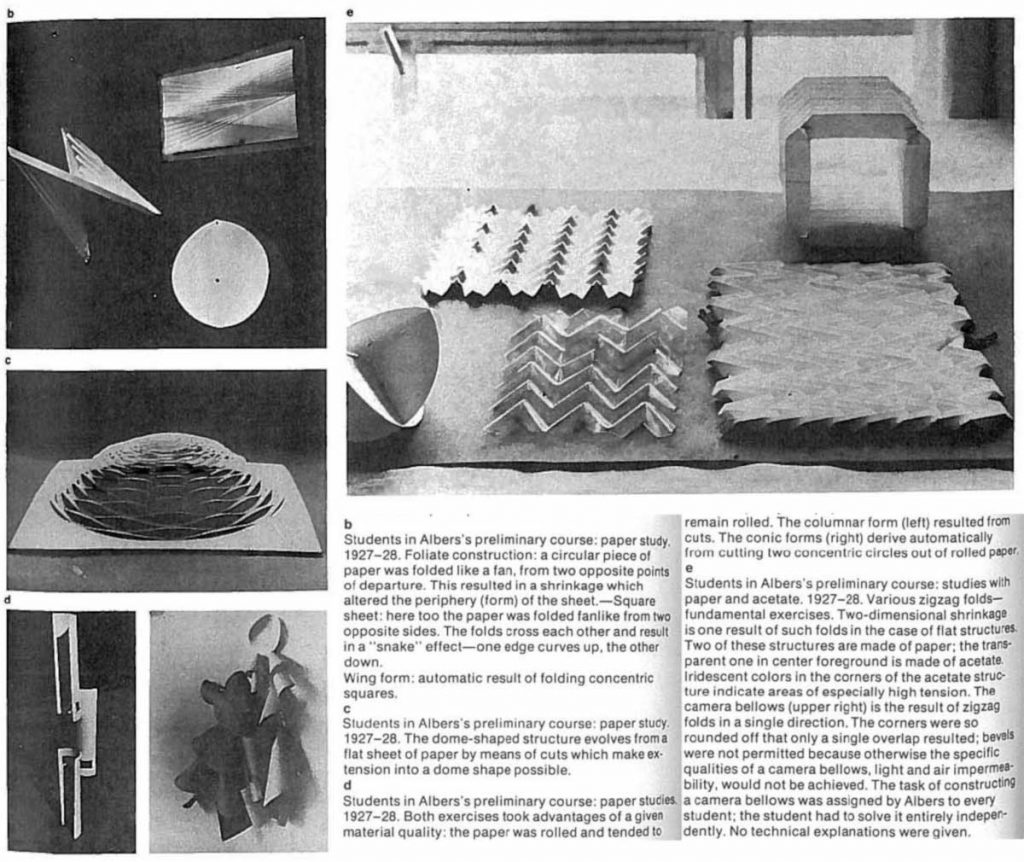

Talking about origami means taking into consideration the many facets and applications of this art, only superficially associated with children’s play. The German educator Friedrich Froebel (1782-1852), inventor among other things of the kindergarten, was an active proponent of origami and its educational benefits, associating his activity with regard to three basic types of folds: the folds of life, the basic folds to introduce children to origami, the folds of truth, to teach the basic principles of geometry, and the folds of beauty, advanced techniques based on geometric shapes up to the octagon. German contributions to the art of paper folding came even from the Bauhaus movement, where paper folding was used in design schools to teach students the elements of commercial design, as artist and teacher Josef Alber masterfully did.

Spanish author and philosopher Miguel de Unamumo (1864-1936) discussed origami in many of his works, going so far as to use it as a metaphor for his deeper discussions on science, religion, philosophy and life, and even in more recent cinema , as in Blade Runner (1982), origami is used for the representation of almost subliminal messages by Gaff, Deckard main character’s colleague, using the hen (cowardice) or the unicorn (purity but also extinction) to launch indications to the subconscious or to insinuate doubts, and all the actions carried out around these small paper artefacts by movie characters can themselves indicate behaviors that, resulting in psychology reactions, add further interpretations of launched messages.

Reduced to the bone, the art of traditional origami involves only the folding of the paper: cutting or glueing is not allowed, while it is possible to joint several parts. And also in the preparation of the paper, whether square or polygonal, the cut is done by hand without tools such as scissors or blades, simply by exploiting the reduced resistance of the paper where it has been folded, which at the same time constitutes the guideline. Finally, there is no possibility of colouring the origami once finished, the colour rendering must only result from the different colours on the two sides of the paper. In its essentiality, we begin to have glimpses about what the real complexity of this art is, and the similarities that I like to find, as usual, with other arts, also in this case with art of the sword: I began to perform origami many years before picking up a sword, but only looking back I realise those intimate interconnections between the two arts.

To begin with, folding (oru) a sheet of paper is not so different from cutting (kiru) in iaido: in both cases it is an action that must be prepared, mentally and physically, to be trained and improved over time. It may seem trivial but the indecision of a cut that will lead to an incorrect kata is the same as a fold done in a hurry, without care, without training. The fold must be clear, sure, definitive, performed with a single breath: as for a kirioroshi, it does not allow second thoughts and, once done, it no longer allows you to go back, it will remain forever etched in the paper and will carry this tare of inexperience or little depth of practice until the end of origami. The origami is classically made with square sheets of paper and you can try yourself to prepare the starting sheet starting from any magazine page and perform even only the two folds on the diagonals of the square to realize how much it is not actually so immediate a correct realisation: diagonals that do not pass through the center, and therefore do not start perfectly from the corners, folds that show as a sort of smudge instead of being clear like a successful cut, are just some of the problems encountered in the art of folding paper, not unlike performing a kata. And as the folds increase with the complexity of the origami, the similarity increases with the execution of a kata increasingly articulated in terms of riai, kikentai and spatiality.

Like sumi-e, origami is an art that requires tranquility, serenity and patience, to be faced with the right mood and without haste, exactly like iaido: very intimate, and like shibori, origami returns a feeling of joyful surprise, especially using paper with two sides coloured differently, when fold after fold, the colours appear side by sides and opposites, the shapes begin to take it form, up to the last fold that will close the origami as the final repositioning on the kaeshisen in a well performed kata After all, even if we are not experts in origami, in our sword art practice we are used to folding the gi according to very precise rules, to give an orderly and codified shape to our uniforms, a part of which, the hakama , among other things it is characterised by folds whose names represent their deepest meaning: gi (justice), rei (respect, etiquette), yu (courage), meiyo (honour), jin (compassion), makoto (sincerity) and chu (loyalty). But we may also think about how we tie the hakama-himo over the folded hakama, or the shape we give to the sageo knot at the himo, or even the butterfly knot typical of the sageo in the expository koshirae of a shinken. In a certain sense we already have some bases of coded folds oriented towards obtaining a definite final shape. With origami we have the possibility to add a further artistic form to these principles and combine a further practice with that of the sword.

With origami it is possible to create any shape and structure, but the crane has a position of honuor, if not only for the fact that this animal is a symbol of luck: according to the Japanese tradition every thousand folded cranes one cab have a wish to be fulfilled. The thousand cranes are also at the center of a sadly famous story, the one of Sasaki Sadako, who survived the Hiroshima bomb but later contracted leukemia. Sadako began to create paper cranes for his own healing and eventually with the intention and hope of being able to bring peace to the world. Unfortunately, she managed to complete only 644 of them, while the remaining cranes were built by her schoolmates and were buried together with the unfortunate girl, to whom the Monument to the Peace of Children was later named, the Genbaku no ko no zo (Statue to the children victims of the atomic bomb), erected in the Hiroshima Peace Memory Park and which houses thousands of origami cranes coming from all over the world.

To practice origami, one can use any type of paper, considering however that the thickness, or the weight, could be a limit: an extremely thick paper will be very difficult to fold, and the folds could also break, while a paper that is too thin, although it can give results of an outstanding lightness especially to three-dimensional origami, it may not be able to maintain its structure. But to familiarize yourself with the folds, even a newspaper or magazine can be effective, without wasting more valuable papers: the fact that such paper also has images and text on both sides helps to create works with highly random “colour” effects, making it an even more enjoyable practice. Paper is therefore a very important factor in the art of origami as well as the relationship with the artist, as perfectly expressed by Hatori Koshiro, a Japanese master of origami, with the words “I have the feeling that my works are a collaboration between paper and me “. Finally, the most precious origami papers can be used to create the final works once a little preliminary experience has been gained and to enhance the structure down to the smallest detail. Precisely for the reason that any common paper support can be used to work with origami, explains why this art is often applied to childhood education on the most diverse themes which can range from mathematics to geometry, as well as problem solving and to the relative open-mindedness required, with the added value of the lack of judgment on the right-wrong dichotomy, teaching that there are many ways to arrive at a solution, and also enhancing the value of accepting defeat or failure, perceived as a process of trial and error, and consequent modification of the actions to arrive at the solution.

Crane, box and noshi: a few basic origami examples made with recycled paper from magazines.

It is no coincidence that the application of origami is often the basis of much more complex disciplines applied to the creation of highly technological objects, where precision, effectiveness, elegance and economy are required to achieve the goal: once again it cannot jump out the similarity with the art of the sword, where the entire path of improvement is given by the cleaning out process deriving from the elimination of the excesses that are inevitably introduced in the beginner learning phases. And these are also some of the reasons why NASA engineers heavily relied on origami to build high-tech projects like folding telescopes and flower-shaped shields to block radiations, and similar algorithms for folding are what led to for example the creation of the airbag or the creation of pop-up shelters for the homeless. To remain closer to the some national architectural works, even Reggio Emilia high-speed train station can be seen as a gigantic modular structure of origami inspiration.

Whether it is considered as a game for children, the basis of an engineering science or an art characterised by manual skills, the beauty and fragility of origami represent, in Shintoism, the life cycle and the end of things aimed at a continuous rebirth. Those who admire the beauty of origami accept the fact that, however tiring its construction might have been, it is anyway a temporary object, which at a certain point will exhaust its function and disappear. The Japanese once again find in all this a remarkable poetry and profound philosophical and moral implications, but it is extremely easy to love this art even for us Westerners since the first contact with paper, as simply as to be able to create small artwork literally from nothing.

lele bo

Resources:

- https://www.thesprucecrafts.com/brief-history-of-origami-2540653

- https://www.britannica.com/art/origami/History-of-origami

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/22/arts/design/modern-origami-art.html

- https://blog.redooc.com/larte-e-la-scienza-degli-origami/

- https://www.edutopia.org/blog/why-origami-improves-students-skills-ainissa-ramirez